The City Unsettled: An Ecological Ethnographical Approach in Situating Architecture and Urbanism (Fall, 2022)

Closed System: Demolition, Displacement, and Development in East Liberty, Thomas Vite 2022

The City Unsettled is a design-research seminar that tells stories by exploring comics, mapping, intensive actor-network drawings, documentary work, visual journalism, graphic memoir, interviews, and investigation. In the Fall of 2022, we work together unpacking histories and theories about comic, animation, insurgent rituals in cities, and urbanism. Collaboratively, we developed sophisticated forms and content by investigating modes of visual reporting on realities of the world, living or non-living subjects, urban marginalization, hybrid morphologies, and the other. What are existing barriers and deficits of our locality and how do we create better accessibilities to local resources, histories, and emerging prophecies?

By emphasizing the accessible image (Comics) and the Animated documentary, the series of projects contests the idea of a single perspective or clear relationship with reality, instead creating a space where designers can embrace abstraction, combine nonfiction with fiction, and explore critical points of view in unpacking urban ecologies. Research methods around oral storytelling, ethno-ecology, radical mapping, and graphic animations can allow for the exploration of subjects in ways not available to typical architectural and urban research conventions. Notions of ‘truth’ will be investigated through the examination of the broad swathe of animated documentary and graphic journalism, with subjects ranging from family histories, “nature”, racial constructions, immigrant placemaking, war, sexuality, city, and/or play.

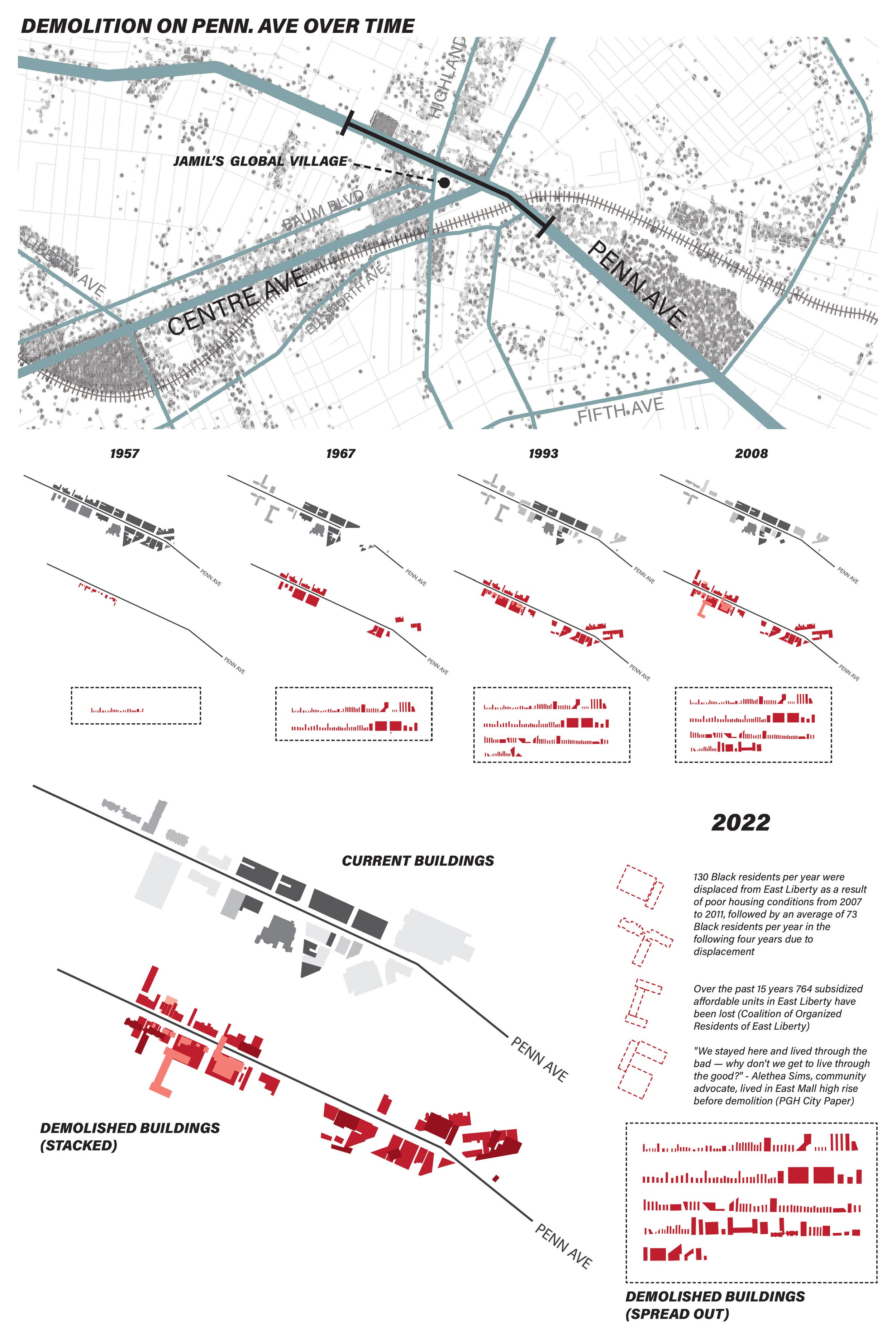

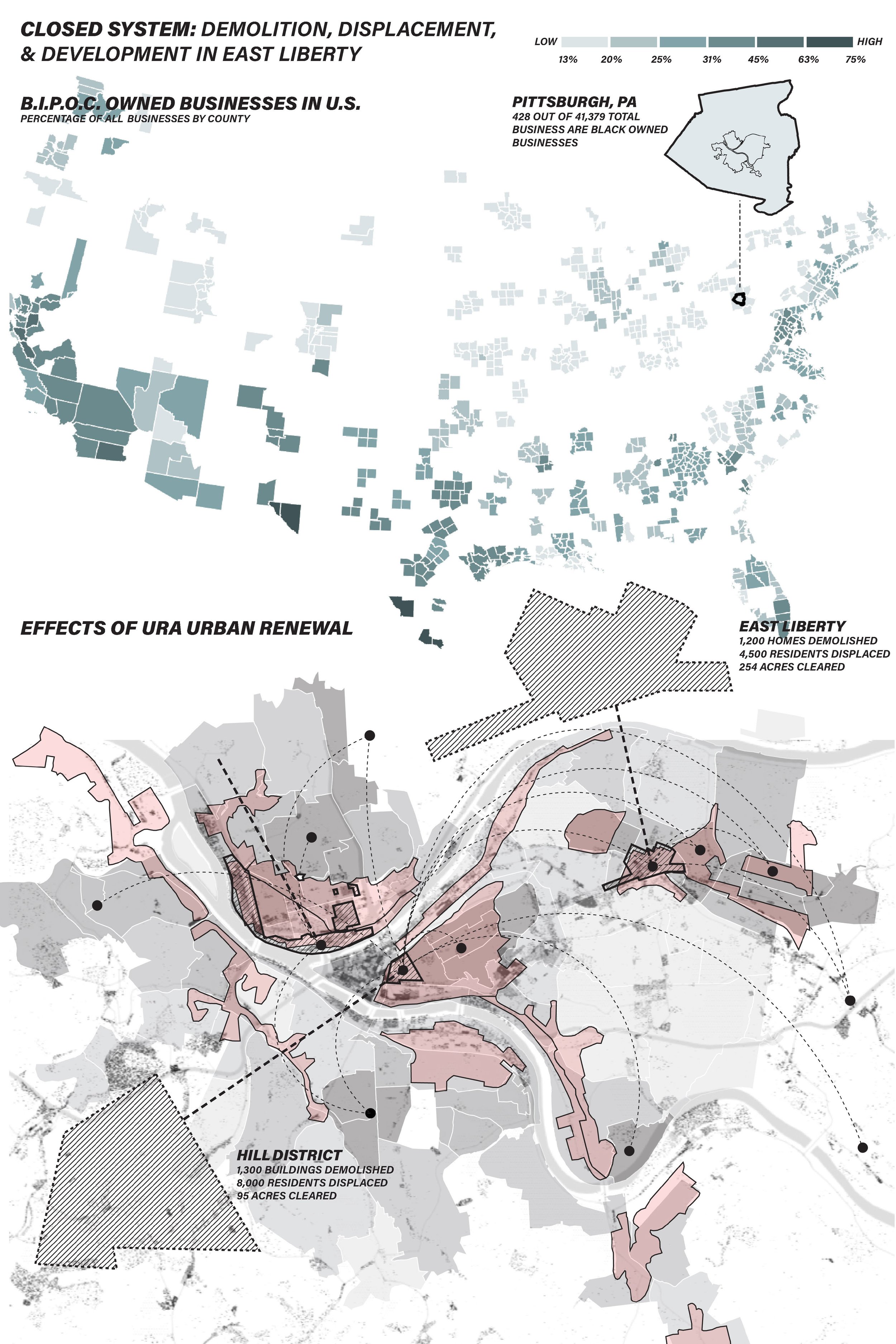

Closed System: Demolition, Displacement, and Development in East Liberty, Thomas Vite

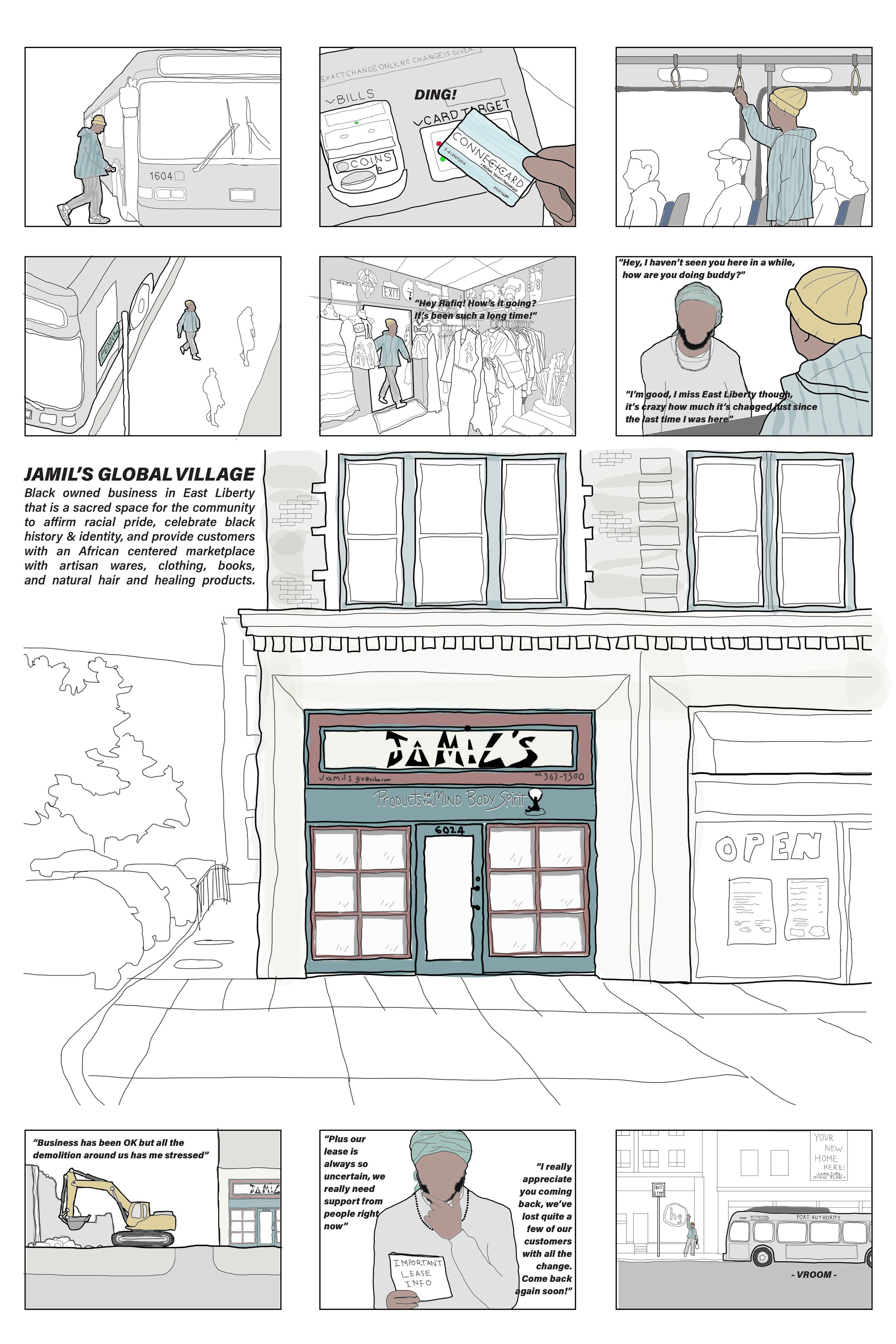

East Liberty has undergone many changes throughout its history and has faced the long term effects of redlining, urban renewal, disinvestment, and now a wave of reinvestment located primarily on Penn Avenue. This reinvestment has contributed to a rapid visual change of architecture, but also a demographic and economic shift that has raised land values and rent prices within the area. When land value and rent dramatically increases like it has in East Liberty, it not only pushes out the residents most vulnerable, but the local businesses and their customers too.

Jamil Brookins, a black and Muslim man from East Liberty, started his business Jamil’s Global Village on Penn Avenue over 30 years ago, which his son Rafiq Brookins now runs today. It is one of just 428 black owned businesses out of a total 41,379 businesses in Pittsburgh. 5 years ago, Jamil’s was on the verge of having to close due to a notice of their lease not getting renewed, but got enough support from local community members and activists to put pressure on the realty company to extend their lease for a couple more years. The illustrated narrative aims to represent some of the ways in which stores like Jamil’s are facing the challenges of losing customer base due to displacement of residents, the effects of COVID-19, the competition of large national chains, the trauma from all the demolitions, and the uncertainty of lease continuations.

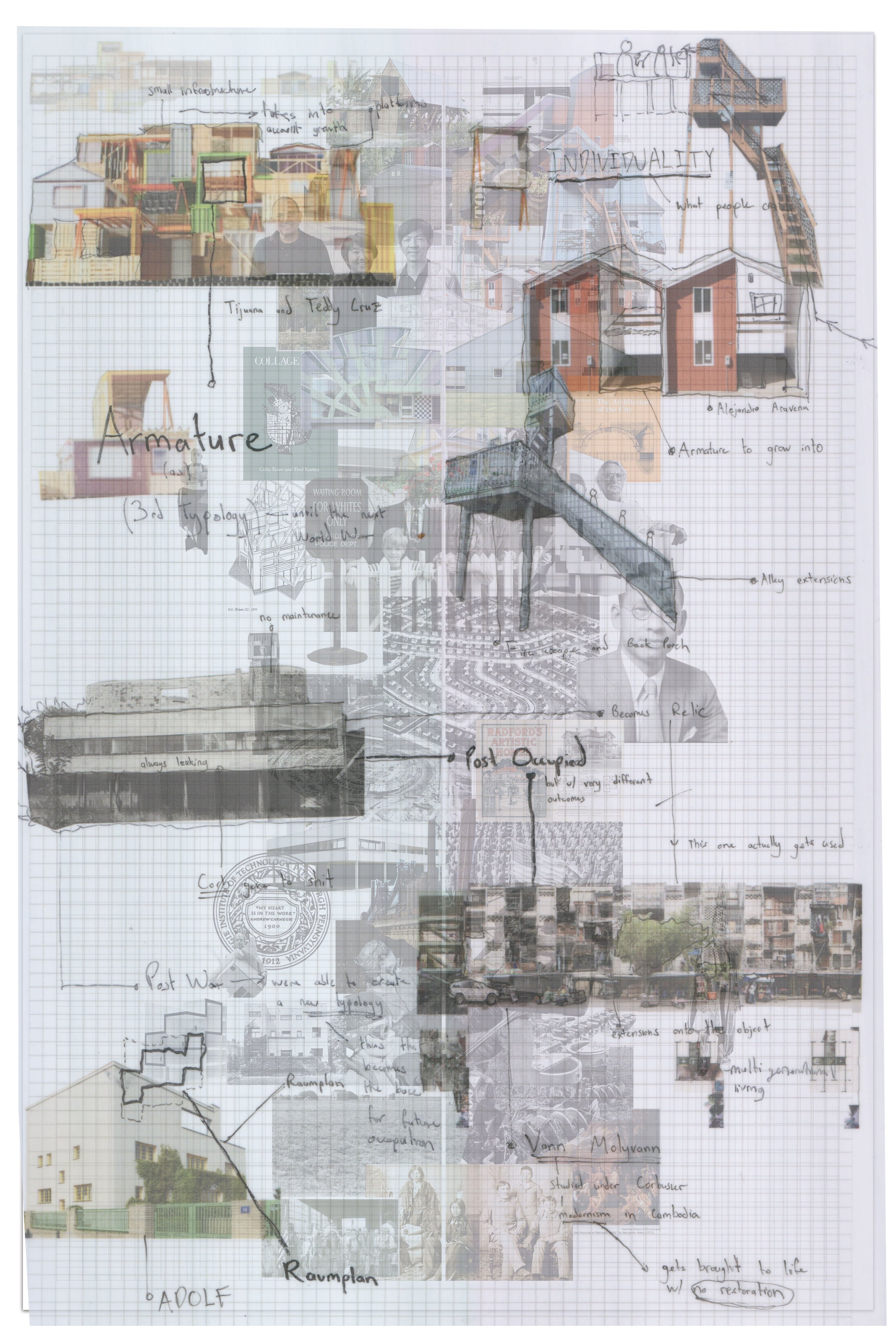

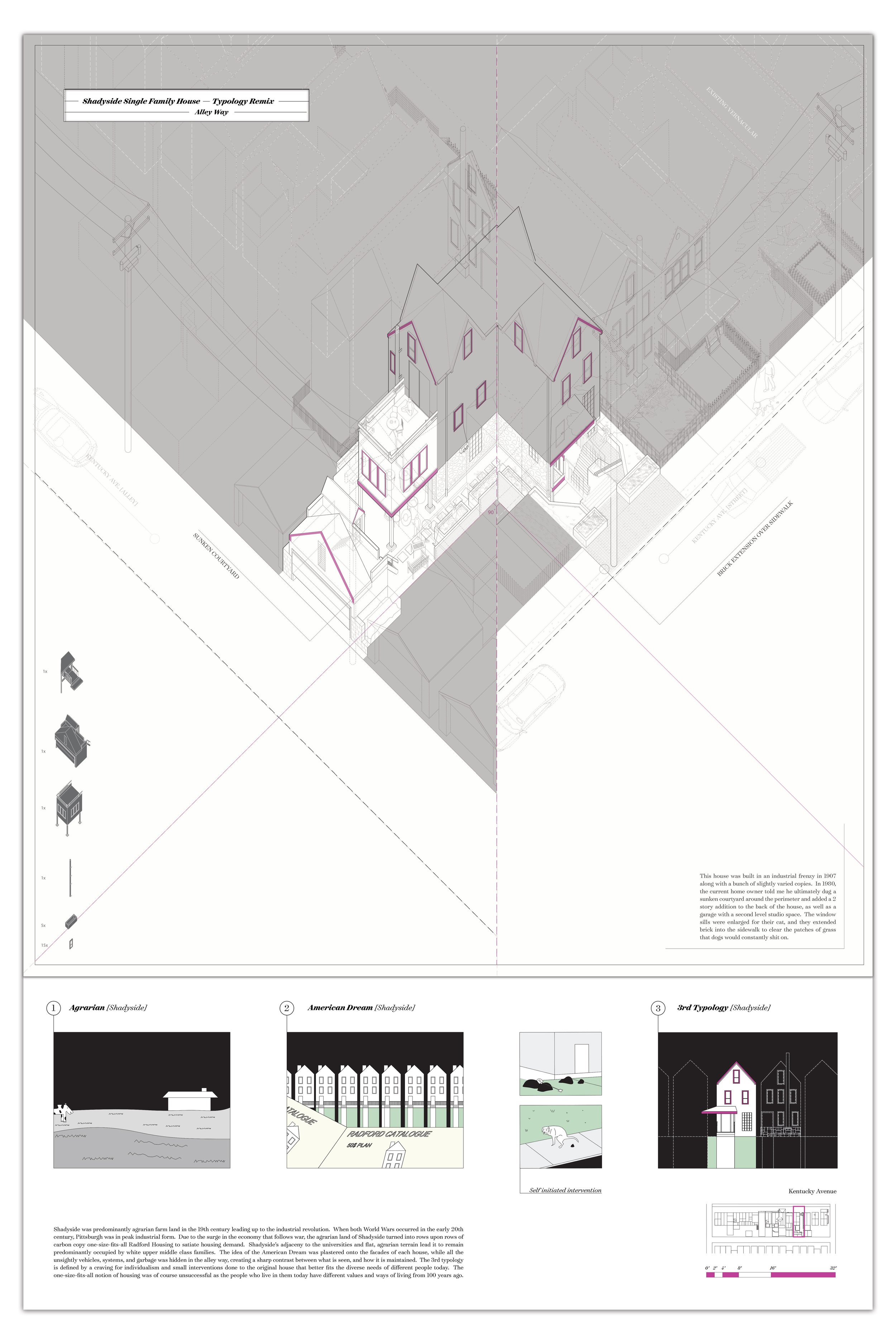

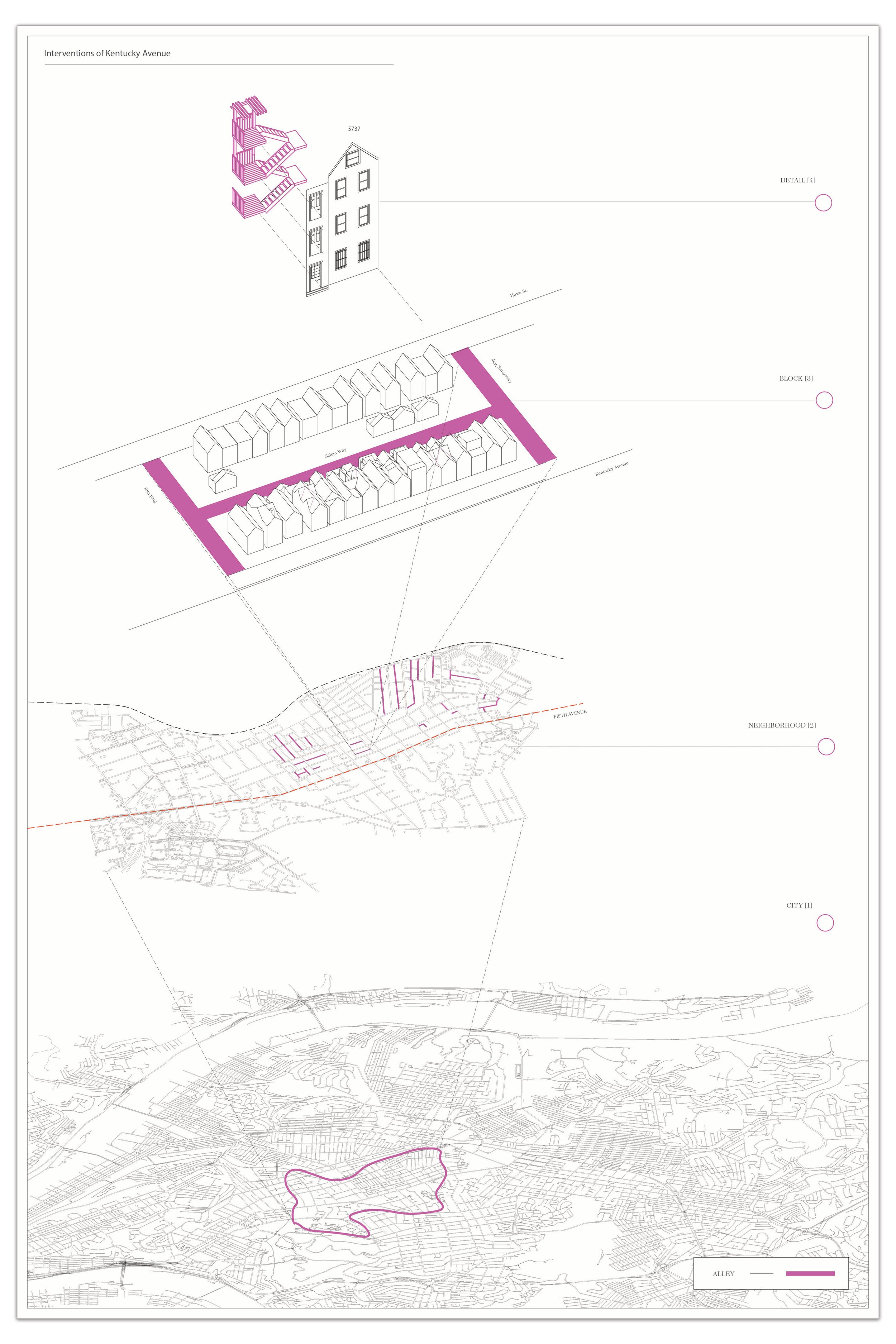

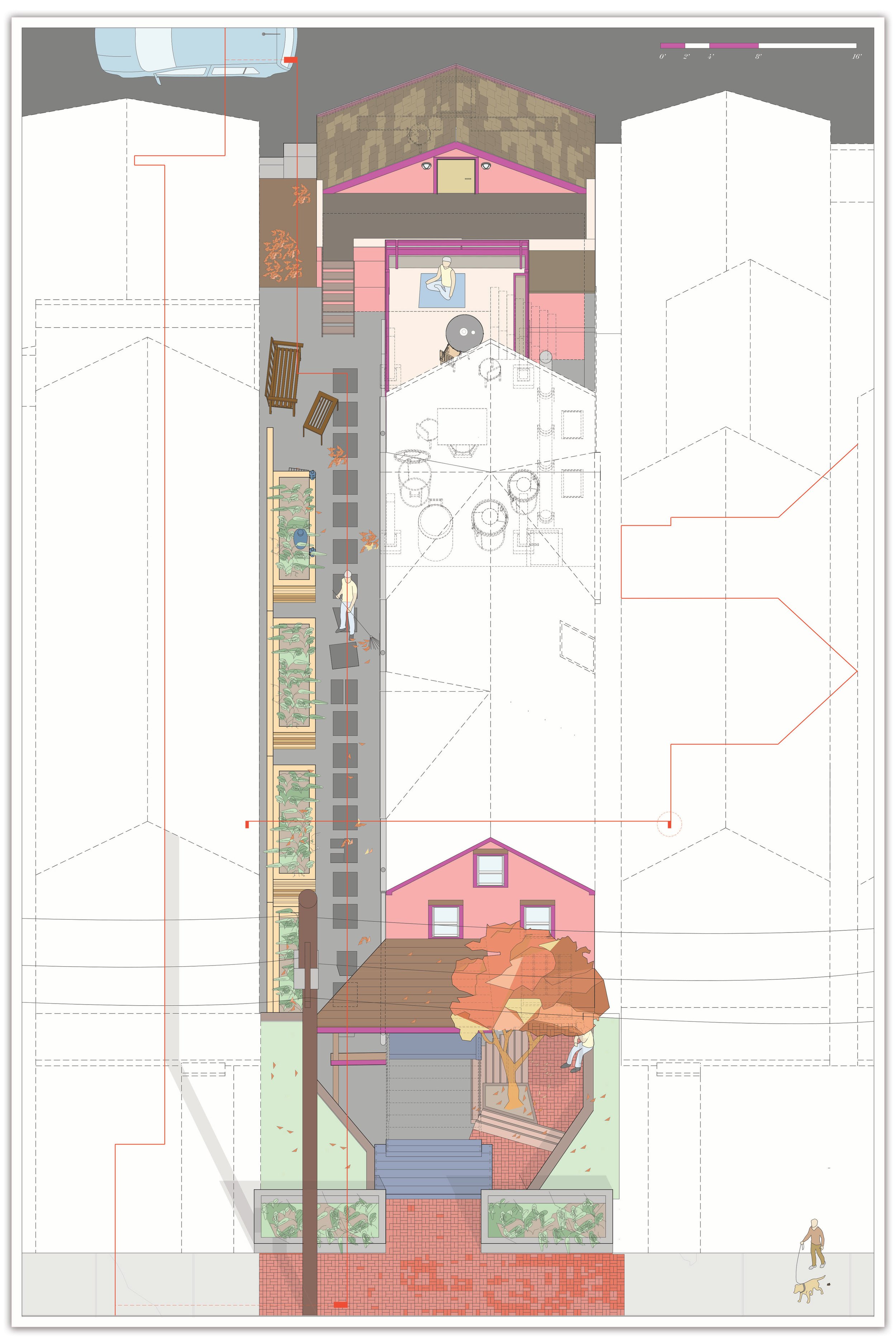

A Vernacular Remix, Brian Hartman

“The type makes us share its particular values and therefore share a culture, while at the same time it allows us to express ourselves as individuals within the culture.”

- John Habraken ‘Type as Social Agreement’

How can the understanding of the vernacular typology of the single family residence of Shadyside be understood as an armature in which the community samples and remixes an American fabric to fit their needs and practices ? My project studies the single family house through the lens of the 3 categories : the spatial, the physical, and the stylistic, posed in John Habraken’s ‘Type as Social Agreement,’ where he argues how and where a formal type in architecture and urban design might have departed from the established vernacular. This social agreement in urban and architectural typo-morphologies can help us as designers and histories of our time to gain insight into how Historical, Social, and Environmental Time influenced the evolution of certain parts of this building type. In the creation of a functional dwelling, urban and architectural typo-morphologies reacts to communities' notions of belonging, ultimately reflecting the way their homes are perceived and thus occupied.

Walking and studying the vernacular fabric of the townhouses dominating Shadyside, my semester unpacked the advertised traces of the white, heteronormative, American dream that largely grew after the World War and the rise of the Kit-Of-Parts Housing Industry in American Cities. With the Post Industrial and Post War boom of housing, a ‘one size fits all’ way of organizing and planning space had been set as the standard with builder pattern books like Radford Publishers filling upper middle class neighborhoods with easily buildable and repeatable products. With many of the blocks of townhouses holding alleyways, the unsightly but necessary spaces of parking, trash cans, and storage could be separated all together from the idealistic image of the perfect neighborhood block advertised on the front face of the houses. Thus a paradox is created, where the main sequence of entry for most residences is separate from the idealized mask worn on the street side. Topographically, and spatially, the terrain and layout of Pittsburgh always positioned Shadyside in privileged, agrarian isolation, defined by its proximity to the Mansions on 5th, university campuses, and its separation from the industrial guts and factories of the blue collar worker.

With the rise of globalization, and the dispersion of the American Industries, today we can see a rise in the Modernist and Postmodernist movement having a strong foothold in Shadyside where many of the ‘Starchitects’ such as Meier, Gropius and Breuer, and Katselas all built their own vision of how one should dwell, departing vastly from the established vernacular surrounding them, and creating a strong distinction between adapting to life and re-proposing it all together. My series of investigations this semester offers a counter narrative. What if the knowledge of the architect drew on the existing fabric and studies the small acts of families adapting architectural layouts and fronts to their own needs?

Using Atelier Bow Wow’s method of research - from on-the-ground field work and rigorous drawing techniques I unpacked how the residential neighborhood nurtures an eco-system of publics and stewardship. The everyday “Da Me” architecture can be thought of as “on '' or “off” as well. When differentiating between alleyway, front yard, and enclosure, Atelier Bow Wow’s three classifications apply: category, structure, and use. The overlap between how these different parts of the residence are either “on '' or “off” and how they bleed into the neighborhood block are suggestive of a greater potential of mixed community uses.

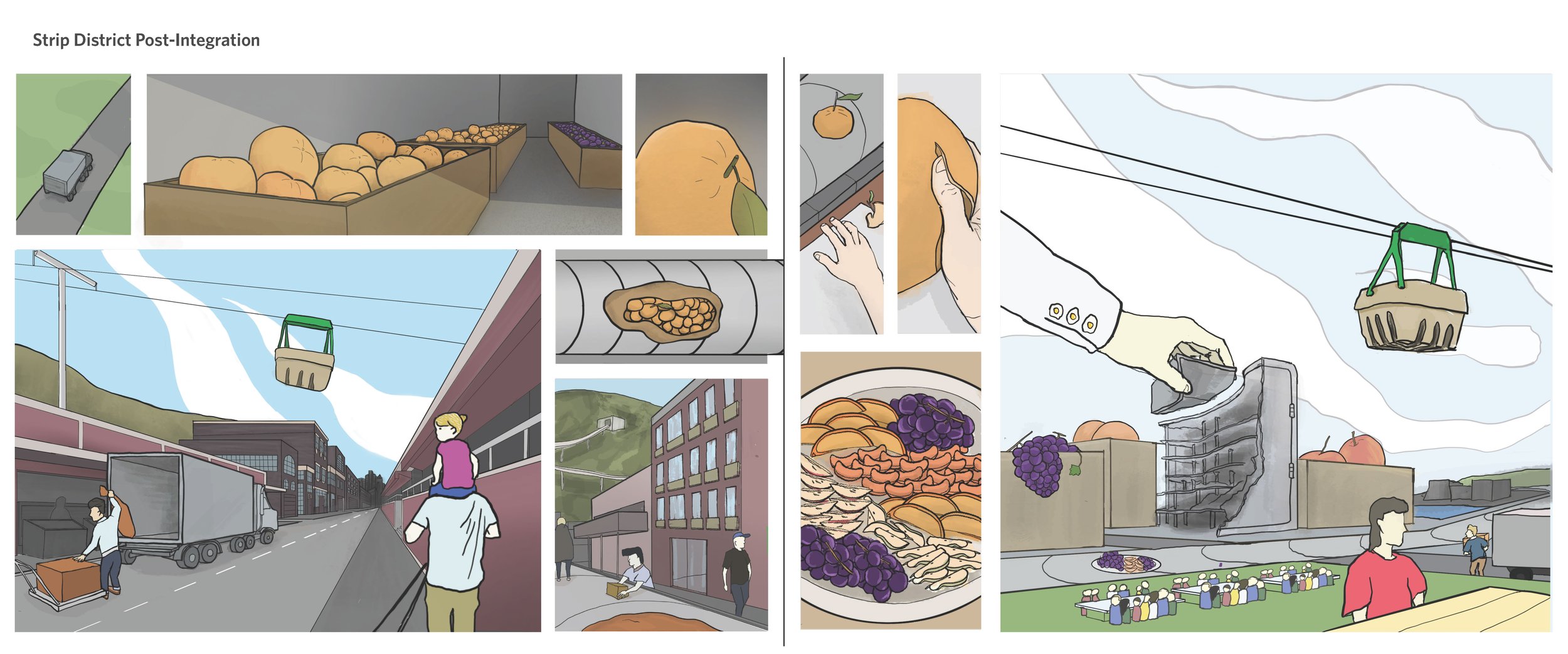

Re-Imagining Pittsburgh’s Food Landscape, Dickson Yau

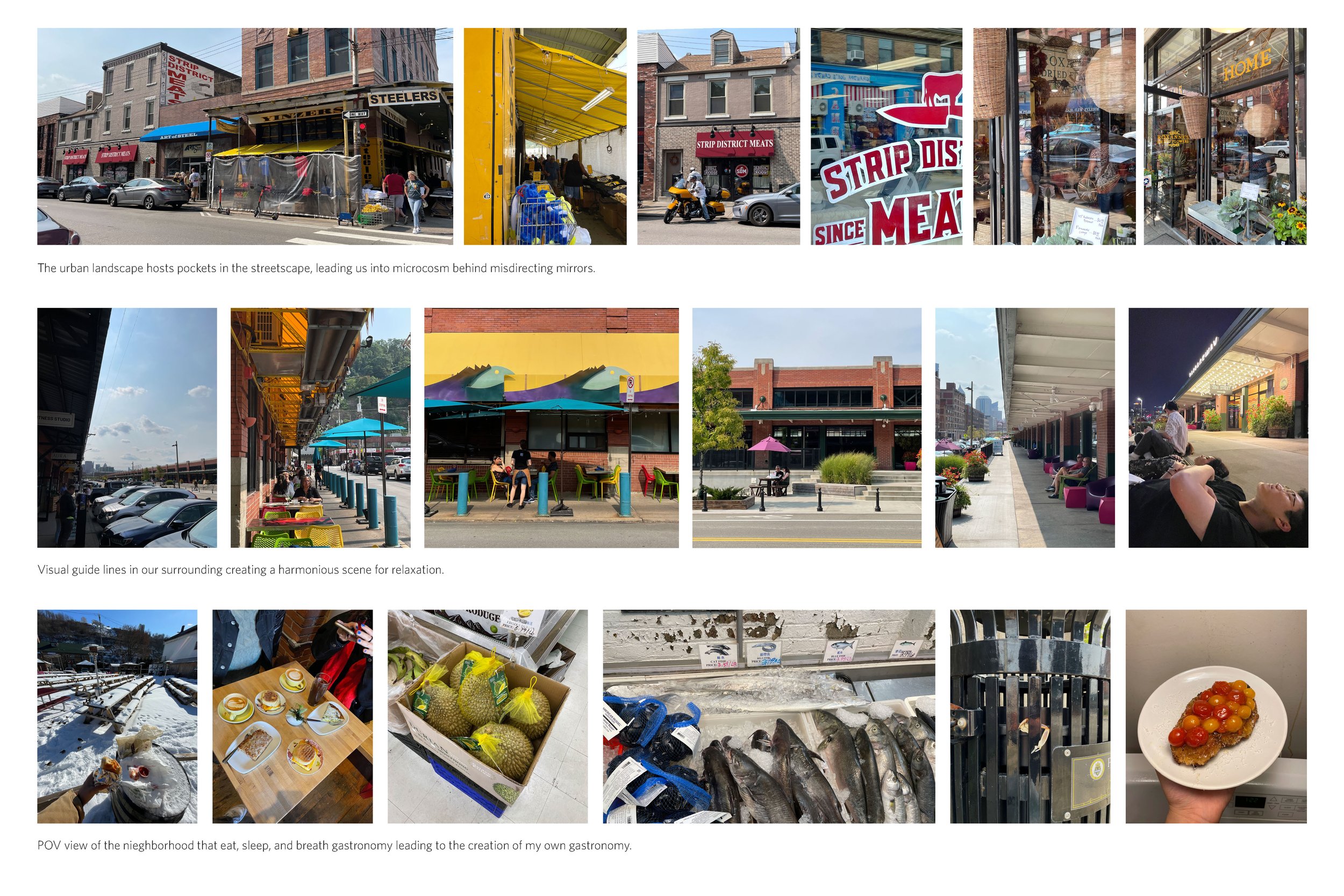

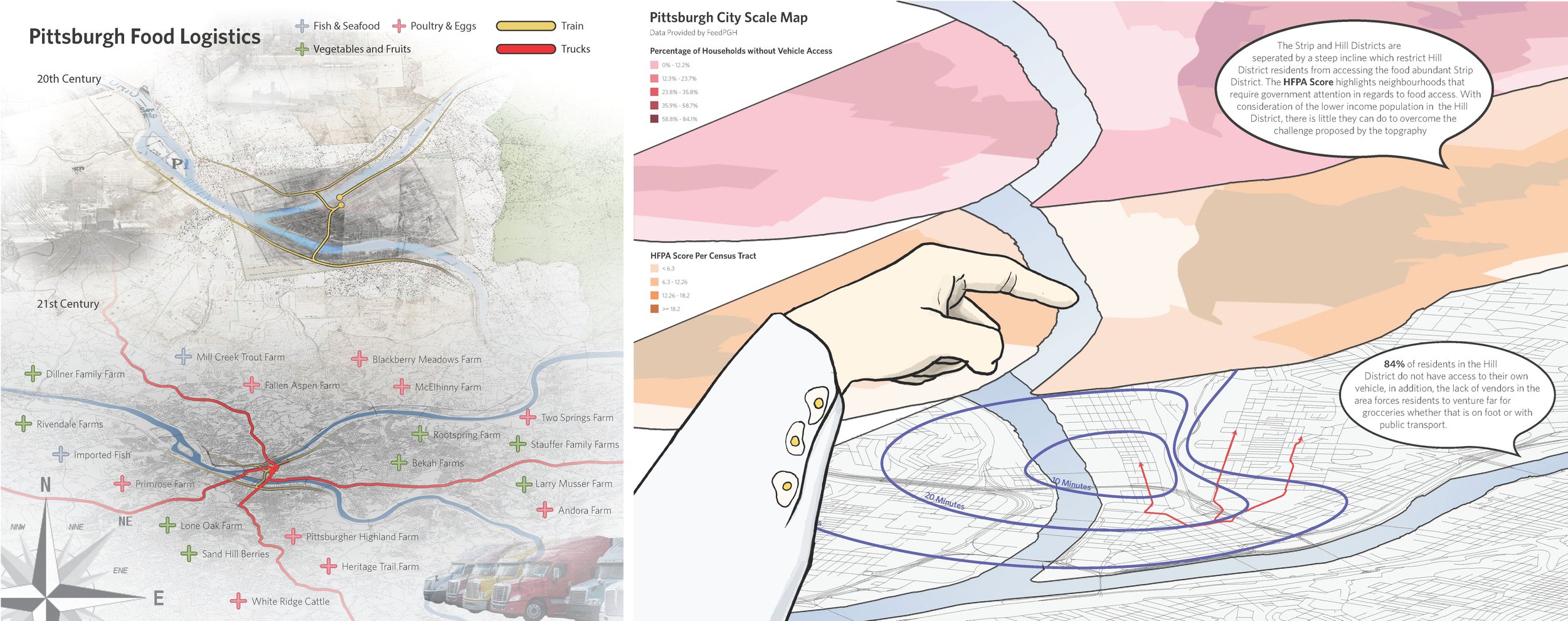

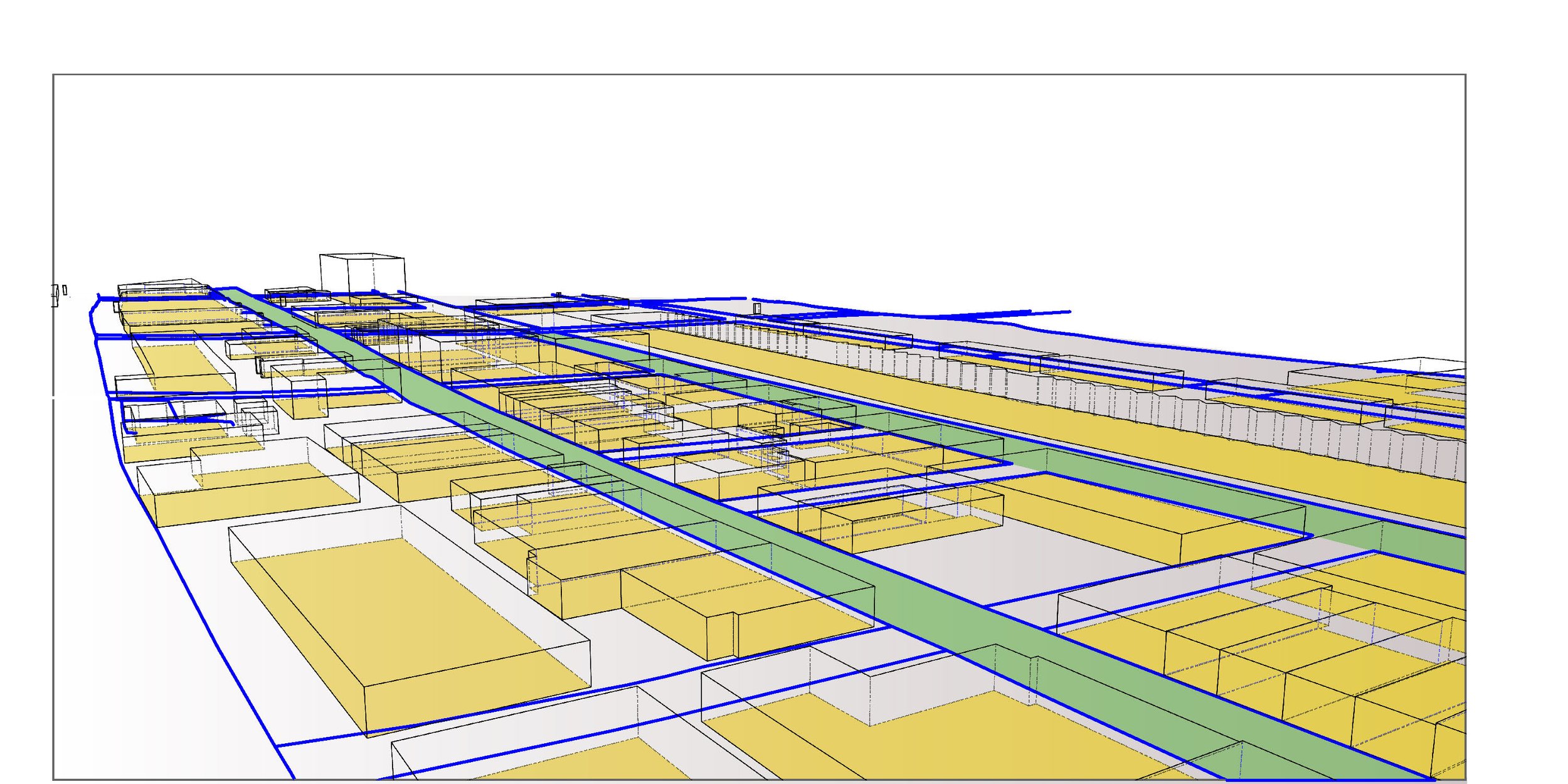

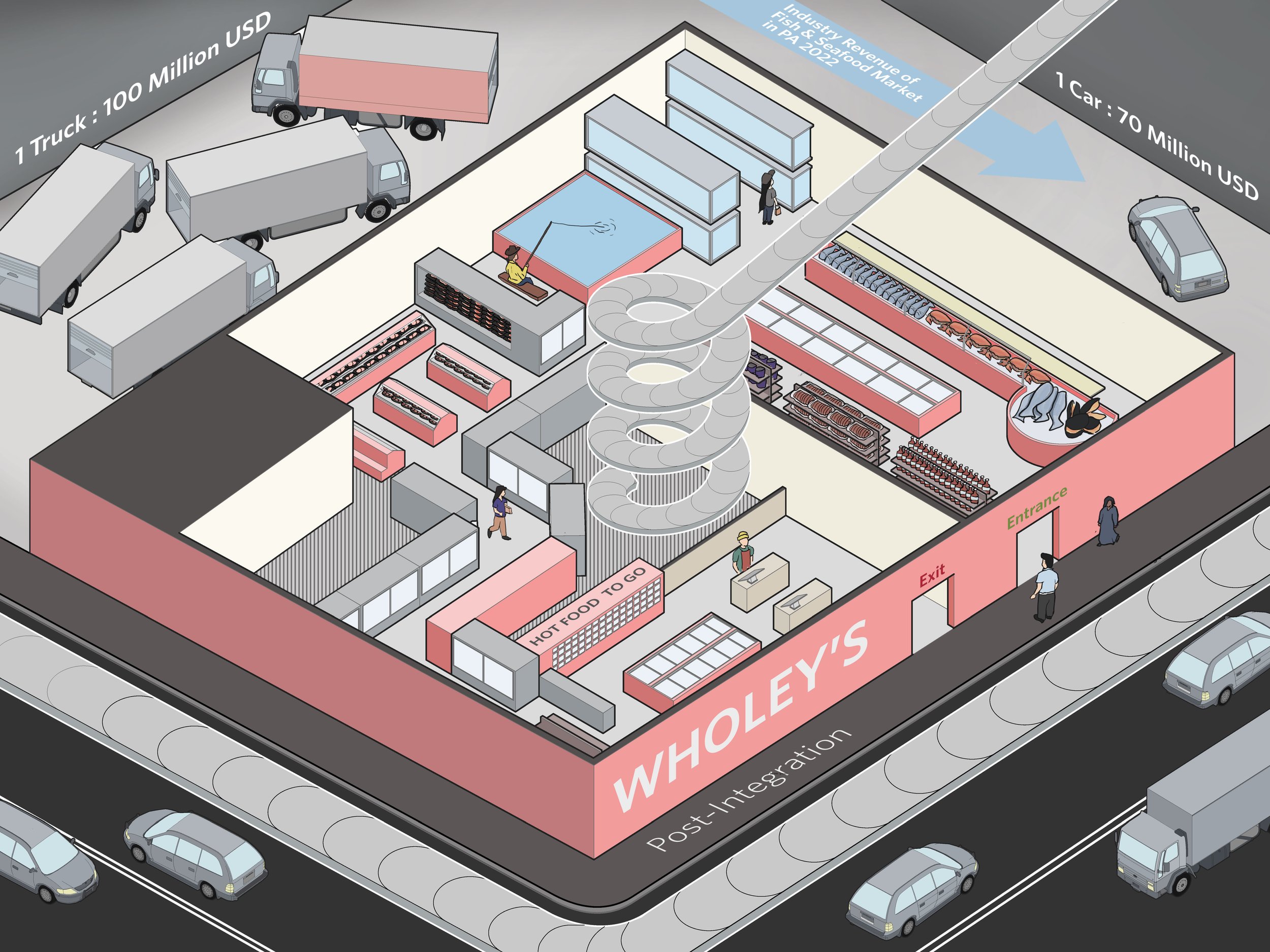

The Strip District has always played a prominent role in Pittsburgh since its early days. The Strip district had a bustling past that rooted itself, like many other neighborhoods, in the steel industry. The close proximity to the river made it an ideal location for transporting industrial goods. However as the industry expanded, the nearby steep hills prevented the industrial facilities from expanding as the market demanded, as a result, the heavy industrial facilities moved east to where Lawrenceville is today. In the post-industrialist age of the Strip District, it acted as the center of commerce for wholesalers in the tri-state area and more. The convenient proximity to Penn station and the train shed allowed the Strip district to become the first stop for most of the food that goes into Pittsburgh. This led to the creation of the auction hall and freezer building.

With a history deeply rooted in food, the strip district continues to fail at addressing equal access to food. The residents in Hill district and Bedford Dwelling have low access to food and vehicle access due to poor city planning. Strip District has the ability to support several neighborhoods’ food needs with its culturally diverse and wholesale-priced offerings, the lack of infrastructure to overcome the steep hill has blocked residents' access to one of the basic necessities of human life. Access to food should be a right for all human beings. In my work, I speculate about a future where access to food is prioritized above all else; physical infrastructures are built to connect Strip District and the Hill District. The process of distribution of food and forms of food served are improved to help simplify residents' eating procedures. The surreal world highlights the disparity of food access in Pittsburgh while portraying the strong presence of food in the Strip District.